Introduction

While Global Citizenship Education (GCE) and Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) are seen as main strategies for enabling sustainable futures, youth around the world are questioning the ability of modern schooling to provide them with the necessary tools to mitigate our current planetary crises (Abebe & Biswas, 2021). The UNESCO declaration Education 20301 highlights the need for the active involvement of youth in education, recognizing “young people as key actors in addressing sustainability challenges and the associated decision-making processes” (UNESCO, 2020, p. 3).

Although educational reform is not the primary goal of youth involved in climate activism, these youth express a distrust in the ability of educational institutions to equip them for creating just sustainable futures. Sustainability education, here understood as encompassing both ESD and GCE, has been criticized for being overtly focused on learning about sustainability, without relating to the lived realities of students, or including marginalized or alternative perspectives (Karsgaard & Davidson, 2023). Simply describing climate issues and social injustice can lead to apathy and climate anxiety (Christie-Blick, 2021; Pihkala, 2020). In addition, Stein et al. (2022) question the potential of sustainable development to inform educational change, given its mainstream operationalization fails to address underlying colonial and capitalist structures.

Based on the above, we argue that insight is needed into how youth reflect on sustainability and the role of education, asking:

How do youth in Norwegian upper secondary schools experience and reflect upon sustainability, and how do they envision the role of education in bringing about change?

The methodology in this paper is a pedagogical intervention study, informed by decolonial pedagogy (Andreotti, 2016). The perspectives of the youth were derived from two interrelated workshops conducted at three Norwegian upper secondary schools. From our material, we see that students clearly call for more critical perspectives related to sustainability in their schooling. However, they also express ambivalence concerning the role of education in enabling sustainable futures, communicating both disillusion with the status quo and a lingering hope in the transformative potential of education. In conversation with the perspectives of the youths, we argue that if sustainability is to provide an educational avenue of hope and change, it requires facing the limitations of modern-colonial habits of being and knowing and acknowledging students as knowledge-producers.

Education, sustainability and coloniality in the Norwegian context

Although commonly anchored in high values of democracy, social justice and sustainability, GCE and ESD have been criticized for upholding neoliberal and capitalist agendas and logics (Huckle & Wals, 2015; Pashby et al., 2020). A related critique is how the operationalization of these ideals in education curricula reproduce discourses that reinforce colonial power relations and imaginaries of the superiority of the white global North (Elkorghli, 2021; Eriksen, 2021; Knutsson, 2018; Mikander, 2015; Pashby & Sund, 2020a). In the Nordic countries, research has identified a long-standing denial of colonial complicity (Keskinen et al., 2019). For Norway, this denial is also intimately linked to the upholding of an exceptionalist national imaginary of superiority in matters of the environment and development (Eriksen, 2018). The incapacity of incorporating coloniality and social justice concerns in environmental projects has recently been displayed through the Norwegian states’ violations of the rights of the Sámi in wind energy projects (Fjellheim, 2023). Although decolonial research does exist within Nordic education research, a breadth of engagement is still lacking concerning approaches that highlight classroom interaction, teaching practice and students’ perspectives (Eriksen, 2018; Sund & Pashby, 2020).

The UN World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) launched the concept of sustainable development in 1987. Although Norway was “active and morally pretentious” internationally, practical politics have often remained restricted to bold formulations in policy documents (Eriksen, 2018). The WCED report (1987) was influential in heightening the emphasis on sustainability in the Norwegian curriculum (Sinnes & Straume, 2017). Yet the engagement with sustainable development has not been consistent (Kvamme et al., 2019). Commonly, environmental and sustainability concerns have been framed within the science subjects, often conceptualized as environmental education and focused on ecology and natural mechanisms (Bragdø, 2022), entrenched in technology optimism (Eriksen, 2018; Sinnes & Straume, 2017).

Interestingly, the newly adopted curriculum in Norway, stating values and principles that are to guide all curriculum development and educational practice, affirms sustainable development as one of three overarching topics. The approach to sustainability emphasizes critical thinking and exploratory learning (UDIR, n.d.a). Eriksen & Jore (2023) argue that despite the sanctioned ignorance of coloniality in Norwegian education discourses, the new curriculum opens for the integration of such perspectives, notably through the renewed emphasis on power-critical thinking.

Methodology

The methodological approach in this paper is embedded in decoloniality. At the heart of decolonial research is “transforming the world by transforming the way people see it, feel it and act in it” (Tiostanova & Mignolo, 2012, p. 131). Hence, decolonial approaches recognize that knowledge production is situated and political (Eriksen & Jore, 2023). We maintain that research that is openly value-based is neither more nor less ideological than research claiming value-neutrality; rather, it is a question of the extent to which intentions are transparent. Our approach is not concerned with an alleged universal representation of ESD and GCE in Norway, but rather with mobilizing knowledge to challenge and interrupt current modes of thinking and inspire new conversations that recognize and acknowledge marginalized perspectives (cf. Eriksen, 2021). As decoloniality is both analytical and practical, the approach refuses any alleged separation between data and analysis, or method and theory. Next, we will account for the theoretical framework and methodology that form the basis for the discussion.

Theoretical framework

Although decolonial theory has seen an insurgence within academia, the mobilization thereof is lacking within practice and research concerning ESD and GCE (Eriksen, 2021; Sund & Pashby, 2020). Decolonial theory confronts colonialism’s present influence on systemic power structures and how mainstream notions of development, progress and sustainability negate marginalized perspectives born of past, and present, injustices (Pirbhai-Illich et al., 2017; Tiostanova & Mignolo, 2012; Zavala, 2016). This dominion encompasses both ontological and epistemological spheres in which other ways of knowing and being outside the modern/colonial Eurocentric frame are relegated as inferior; “validation” of such is only possible from within the very frame that negates it (Santos, 2015). The inability to deconstruct the ongoing Colonial Matrix of Power (CMP) can be further understood through the analogy of the shine and shadow of modernity (Mignolo, 2007). The shine of modernity represents mainstream notions of development and progress, and the possibility thereof only due to the ensuing shadow; i.e., the suffering and exploitation of “others” from an ecological, and onto-epistemic level (Andreotti et al., 2015).

Andreotti et al. (2015) offer a social cartography of approaches to decolonizing education, mapping three “spaces of enunciation”: soft reform, radical reform and beyond reform (see Table 1 below). Described as a pedagogical tool, the cartography represents different educational modalities of hope one mobilizes to incite change, and sheds light on the “contradictory imaginaries, investments, desires, and foreclosures that arise in efforts to address modernity” (Andreotti et al., 2015, p. 23). The sphere of soft reform denotes a linear model of progress enveloped by the shine of modernity and the overriding goal of entrance to therein. There is no depth of criticality of the ensuing shadow, and any barrier towards entering the shine is relegated to the individual level (Andreotti et al., 2015, p. 26). Though within soft reform there is an emphasis placed on inclusion, in other words participation in current modern neoliberal economic structures, it does not address systemic barriers. Within the sphere of radical reform there is a wider acknowledgement of structures that obstruct access to the shine. Interwoven within is the premise of empowerment, with a recognition of perspectives marginalized within the shine from both an epistemic and more concrete, materialistic level of redistribution (Andreotti et al., 2015, p. 27). Unlike the soft reform, the radical reform-sphere emphasizes the need to disrupt mainstream ways of thinking through collective action to “fix the system.” However, this sphere does not present alternatives. The beyond reform-sphere disregards the notion that the present system can be “fixed” (Andreotti et al., 2015, p. 27). Within the path of “modernity,” the possibility of intrinsic change required for a just, sustainable future disappears. Though the premises within the radical reform are envisioned as valid points of departure, they are restricted to means for hospicing a modernity in the throes of collapsing. The beyond reform-sphere thus gestures towards a deeper onto-epistemic engagement of transformation. In this paper, we apply the model to explore the youths’ perspectives. Although Andreotti et al. (2015) uphold the model is pedagogical rather than normative (p. 23), it is a major point that the beyond reform-sphere holds greater potential for the transformation needed for providing more sustainable futures. We uphold, with Stein et al. (2022), that the problem with current efforts towards sustainability in education relates to how these imperatives are constructed within the educational frameworks that form the genesis of the problems of (un)sustainability they allegedly are set out to solve.

| Spaces of enunciation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Soft reform | Radical reform | Beyond reform |

| To make the same system a little bit better through transformations of policies and practices. | To make the same world a lot better by including more people, voices and perspectives in collective action. | To disinvest in the current unsustainable world and walk with others into the possibility of new worlds. |

| Horizon: Single story of progress, development and evolution | Horizon: Unification of many voices in a single direction | Horizon: Learning from repeated mistakes in order to make different mistakes, change “way of being and co-existing” |

| Same questions

Same answers |

Same questions

Different Answers |

Different Questions

Different Answers |

| HOPE for CONTINUITY of the same system | HOPE for FIXING the system | HOPE for OTHER systems |

Method and materials

The main method applied in this paper was a pedagogical intervention study, where Author A entered the classrooms as a teacher-researcher (Kincheloe et al., 2018). Two interconnected workshops were designed and conducted at three separate Norwegian Upper Secondary Schools with a total of 42 participating students, with an average age of seventeen (Roberts, 2022). The upper secondary schools were geographically situated in median income areas with predominantly white students (commonly referred to as “ethnic Norwegians” in Norway), in conjunction with a smaller number of those with racialized immigrant backgrounds. The students worked in seven separate sample groups with approximately six participants in each group. Interaction and conversations in the groups were recorded via GoPros resulting in approximately eighteen hours of video-recorded data. The pedagogical design was based on decolonial approaches to ESD and GCE (Andreotti, 2016; Andreotti et al., 2018; Darder, 2020; Freire, 2018). The workshops focused on a dialogical, learner-centered approach that supported critical thinking, the iterative process, and emphasized a tactile, creative experience. The intention was to open a space for participants to reflect together on the CMP, the shine and shadow of modernity, and on how the educational spaces they inhabit (im)mobilize mainstream and marginalized perspectives towards sustainable just futures.

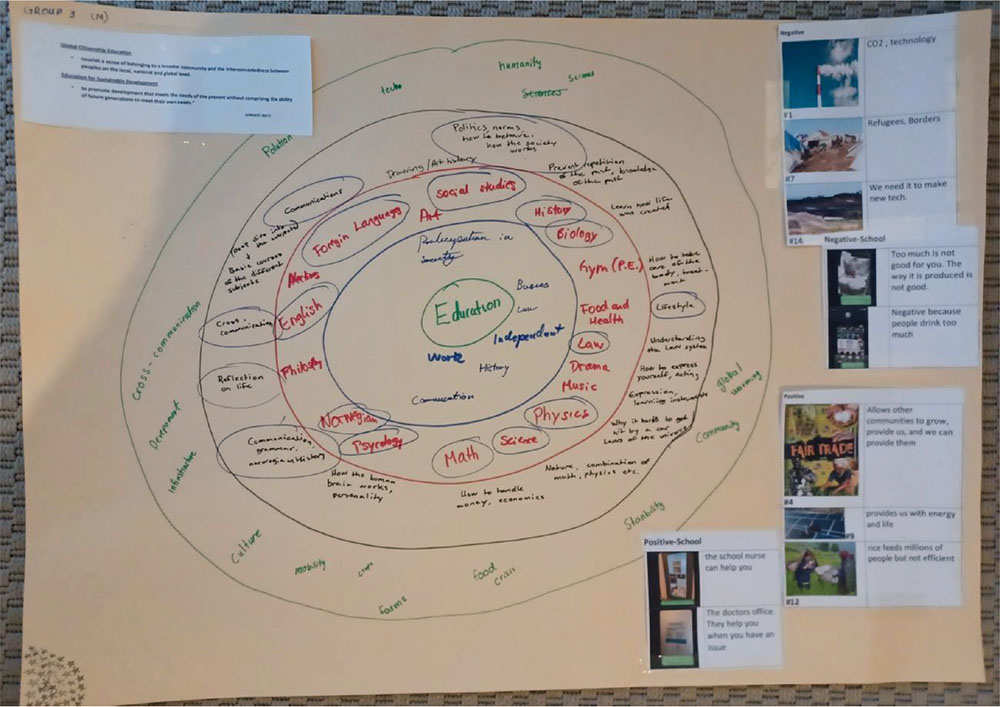

The point of departure for participating students was a brainstorming activity conducted on poster boards. Their reflections were further mobilized by applying the pedagogical tool HEADSUP (Andreotti, 2016) and its integration with the photo elicitation method (PE).This method enabled a creative, tactile, dialogical approach in the workshops, and the ability to incite deeper engagement and more depth in the material (Harper, 2002). HEADSUP, set up as an acronym,2 represents a series of questions that moves one towards a critical awareness of how approaches to transformative change within mainstream systemic structures can lead to reproducing historical socio-environmental oppressions (Andreotti, 2016; Pashby & Sund, 2020b). Proceeding a whole class mind mapping activity based on the HEADSUP tool, students were introduced to sixteen hard copy images representing different concepts of ESD and GCE. The aforementioned were predominately furnished from educational texts on citizenship and sustainability. In smaller groups, students were encouraged to engage with the images in the context of their positive and negative connotations with sustainability. The workshops resulted in student posters (Image 1), which remained with the participants as a point for further reflection.

Image 1. Example of final poster boards. Education was first written in the inner circle. The secondary inner sphere represents student reflections on the goal of education, then working outwards, the subjects taught, and skills and knowledge gained therefrom. The final circle was added following the mobilization of HEADSUP, with students directed to brainstorm the words/concepts they associated with the “goals” of ESD and GCE. Students then circled the subjects, knowledge and skills that supported the aforementioned and added anything they felt had been omitted. Photos and sentences included were chosen and written by students.

Analysis

An initial thematic analysis supported “analyzing, organizing, describing, and reporting themes found within a data set” (Nowell et al., 2017, p. 2). This approach was complemented by a critical discourse analysis, in which data was analyzed as a whole, allowing an examination of not just what is expressed, but also how it is expressed within different junctures of discourse (Bryman, 2016). The discourse analysis was informed and shaped by the decolonial theoretical framework, as described in Table 1 above.

Results: Youth perspectives on sustainable futures

Three overarching topics were derived from our analysis of the students’ reflections: conceptualizations on sustainable development; the difficulty of imagining alternative pathways; and how students perceive the role of education in mobilizing an authentic, just approach to sustainable development.

Conceptualizations of sustainable development

Within the youths’ conceptualizations on sustainable development, there were expressions of a critical understanding of systemic structures that guide, and can impede, approaches towards a sustainable and socially just world. The participants commonly reflected on the tensions around systemic power structures, past and present, and in connection with this, some of them questioned the present emphasis on technological optimism. Their observations indicate an awareness among the students that mainstream notions of progress and modernity have been historically produced and resulted in the present predicament of unsustainability:

I think modernization is the solution but also part of the problem. Globalization and industrialization is what has been causing all these global problems. But also, I think it is the solution for solving the problems. That hopefully it is part to help the future. (Unit2CS2)3

Students hence recognize, to varying degrees, the need to challenge current social systems and structures. Some further emphasize the “need to learn about history, to learn what we didn’t do right” (Unit3BS5). Although the students do gesture towards a critical engagement with history, they appear to be quite unfamiliar with colonial analysis and perspectives, and in need of more precise conceptual tools to help them articulate these notions more clearly.

Though overall their narratives position technology as a key means to mitigate the ecological crisis, much in line with neoliberal discourses fueled by the shine of modernity, the hegemonic placement of technology is questioned by the students. The movement towards a modern ideal is expressed as having gone “a step too far” (Unit2AS1) with the awareness, “its effectiveness has created a global problem” (Unit2AS3). Students expressed how inequitable access to technology results in a disparity of effectiveness of technological implementations globally from both ecological and social perspectives. Participants hence also do seem to recognize how the shine of modernity results in an ensuing shadow (cf. Mignolo, 2007). For some, this predicament is still deemed an inevitable consequence that is mitigated, and validated, by the “other” being given an economic pathway towards the shine. Like Unit1BS1 expresses: “Yeah, of course it affects them, but maybe a positive they can get jobs […] Okay, but it can also hurt them.” Followed by a pause, a moment of deeper reflection, the student continues: “This is hard.” The aforementioned mirrors the workshop’s mobilization of decolonial premises into more accessible reflective forms. Although difficult for the participants to navigate at times, there is a cognizance of the need, and as importantly an appreciation, for this form of disruption in their traditional curricula.

There is also the perspective that the complexities within present day structures hinder a just movement towards sustainability. This is present in the acknowledgement that although economic, environmental, and social aspects are allegedly given equal value in mainstream approaches to sustainability, the economic aspect trumps the others in practice:

So sometimes people think of technology, economic growth, but only cost economic growth, but that modernization and mass production can cause also influence climate change. We can change how we produce commodities and services to make it more sustainable. But we are not doing that because we are putting profit margin above lives. (Unit2CS6)

Participants acknowledge that “Western Countries take advantage of their (those in the Global South) resources” (Unit2CS6). Simultaneously, there is a clear ambivalence and a sense of disillusionment: this predicament also seen as an inescapable consequence within the current framework underscored by capitalist and technological solutions. However, students do recognize the need for change, but simultaneously express they are not given the skills nor space needed to explore what this change could encompass.

Within the material, all of the participants expressed a desire to engage with different answers to the questions and challenges raised by sustainability, as characterized by the radical reform-sphere. However, though the participants wish to engage with the “otherwise” (Andreotti, 2015), the overriding emphasis on technological optimism within the Norwegian context, especially within the sphere of curriculum development (Eriksen & Svendsen, 2020), seems to impede participants to imagine and engage with alternatives in a deeper sense and question the undisputed shine of modernity. Hence, although these reflections display a will to challenge common ways of thinking, criticality is not given the space or tools to gesture towards more transformative approaches to moving beyond (cf. Andreotti et al., 2015).

The (im)possibility of alternative pathways

Although technology-optimistic, neoliberal and progress-oriented frameworks dominated students’ reference frameworks, many also displayed an emerging awareness of alternative pathways. Ways of being and knowing outside the modern/colonial framework appeared as somewhat intangible, imagined outside of the lifeworld of students, or in a different geographical or temporal spatiality. One way this was displayed, was through the relegation of such alternatives to the past:

S3. If we lived like the natives there wouldn’t be climate change

S1/S4. That’s true.

S3. I couldn’t live like that

S1. Like native still on modern in some way

(Unit2A)

In this dialogue, there is, on the one hand, an acknowledgement of Indigenous modes of living. However, on the other hand, this is externalized, imagined as no longer present, and placed outside mainstream, hegemonic development and progress. This echoes the work of Santos (2015) and what he terms as “epistemicide” happening in and through modernity/coloniality, and which devalues knowledge shaped outside the Eurocentric domain. Yet, the students do grasp that this relegation to the past is the result of social injustices. The above dialogue continues to reference the Sámi and First Nations peoples:

S1. Like native still on modern in some way. I mean, I would say Sámi,

S4. They were assimilated into Norwegian culture. Forced.

S1. True.

S4. They had a hard time. They keep their traditions now because they are allowed to.

S3. Before in the sixties, fifties, forties they weren’t allowed to.

Unit2A

Although participants grasp that there are alternative solutions that deviate from modern/colonial perspectives, that have been historically oppressed, they are not able to imagine such ways of knowing and being as having a place as feasible options for sustainable futures. In general, the narrative thread of a linear model of economic development from a historical perspective is well woven into the fabric of climate change understanding among the students. However, the discussion cited above is one of the few instances where a connection is made to the context of historical and social injustice, onto-epistemic genocide, due to the CMP. By relegating Indigenous ways of living to the past, alongside the racialized conceptualizations of “natives as the others,” these perspectives remain externalized and distant from the lived realities, and curricula, of the students.

The externalization of the shadows of modernity from the students’ lived realities is further represented in discussions around the image depicting a refugee camp. Students connect climate change with an increase in refugees/socio-ecological injustices. However, few of the students connect the refugee crisis with historical and present geographic and economic marginalization that is heightened due to climate instability. The refugee crisis is often expressed as a local issue, separate from any wider influences, with poverty the result of underdevelopment, and the unilateral need to “help” those outside the shine. However, throughout the workshops there was one participant who expressed a deeper understanding of the connections between climate change, social injustice and the shine and shadow of modernity:

S1. Refugee camps are always, uh, will always be the consequences of the luxury in which we live… is created by the wealth that comes from the oil in the Middle East, and also the exploitation of the global South. And the consequence of that is, uh, is the endless wars and the sustainability of the region.

S6. But the refugees are also because of climate change.

S1. Yeah, but local climate change that we create, which we…the West will always exploit the global south.

(Unit2B)

As expressed in the original research, this student displayed an ability to reflect on a more profound level on “the inequalities and injustices resulting from the inherent power structures created by the shine of modernity” (Roberts, 2022, p. 78). However, this student’s criticality was seemingly expressed from a cynical position, rather than the possibility for change. This underlines how it is starkly evident that hope is not being nourished for many of the participants. While the students express a disbelief in current economic and social structures, they are not provided with the space or tools to engage more deeply with alternatives where the shine of modernity is not the overriding goal of progress.

The lingering hope in education

Though students envision education as providing capacity for change and sustainability, they express its current form as neither nourishing hope for the future nor giving space for their voices. Participants envision youth as holding the inner power, and desire, for change, but also express the lack of support and tools to empower them to do so; their voices are infantilized. One participant refers to youth climate activism through Fridays for Future and how the movement is often perceived as “we have good actions [that] get overshadowed by the matter of which, how it’s done. It’s just kids will be kids” (Unit2BS1) and another inferring that “the older generation just doesn’t care…it shows we care about the future” (Unit1AS2). This is supported by an adjoining group citing an image of COP26 as “This is just bullshit…” (Unit2BS1) followed with “They’ll get a ton of pay but they don’t care” (Unit2BS4). Hence, there is a sense of frustration in the students’ perspectives on the status quo, and a call for youth being included in the conversation as actual political contributors.

There is a strong sense that their needs are not being met with current educational practices, powerfully described by one student as an “oppressive force and if you are socialized into [it]…then you just accept it further in life. Educational qualification is to create a consumer base in which we consume to the best of our ability” (Unit2BS1). The same participant elaborates at a further juncture in reference to schooling as “the way things always have been to uphold the power structure, because that’s what school is really about.” Though this notion that “we learn to earn”(Roberts, 2022, p. 33) is represented in the brainstorming activity around the purpose of education, with initial responses revolving around the instrumental and individualized economic value of education, of “work,” “career,” “get a nice job,” conversations do osmose into a deeper space of critical reflection regarding what education should nourish.

One overriding concept suggested by all of the groups for educational practices that promote change, to enable authentic engagement with sustainable futures, was creativity. Though broached from varying frameworks, creativity is voiced as important to enable authentic engagement with sustainable futures. Students connect creativity not only to the arts and self- expression, but also as a means “to inspire, don’t force people into like learning shit, like find out their interests, find out their needs, right?” (Unit3AS1) and “get better at things we are interested in” (Unit1AS1). The students underline the importance of acknowledging youth as actual knowledge producers in and through education. Creativity connected to critical thinking is also highlighted: “We think school doesn’t teach creativity and that is very important for problem solving in the future and individuality… to be able to express ourselves and how we think differently” (Unit2CS6).

Thinking differently is broached by Author A in a dialogue on what kind of knowledge is needed to promote sustainable futures, not only from within the educational system but also in conjunction with the concepts of development and progress. When questioned about whose and what knowledge is important, the students respond:

S1. I think educated knowledge… people who are well-educated knowledge is the most important.

S3. I think it’s a combination of knowledges, all kinds of points of view, as opposed to like political, scientifically educationally….

(Unit1B)

While the first participant clearly places mainstream epistemologies and ways of thinking as paramount, the second echoes the decolonial stance/premise of thinking with rather than thinking about (Cortina et al., 2019). Though student participants struggle with pathways to articulate the necessity to engage with alternative epistemologies in addressing the concepts behind ESD and GCE, overall, they do express the need to do so. There is the desire to move away from addressing current issues in silos, towards a systemic, interdisciplinary approach. This is also expressed by the students in their feedback on the workshops:

S5. We don’t usually talk about these kinds of things. Very interesting, educational and fun.

S2. It was interesting to talk about something we don’t talk about a lot unless in these specific scenarios… they’re very important things to talk about.

(Unit3B)

Students express the need, and as importantly, the desire, for more dialogue and interaction in their learning; a conscious movement of the praxis of action and reflection; “Maybe we should do more than just write things down…but talk about it is as well. Why is it important” (Unit2AS1). The students express their desire for spaces to think differently, mirroring to a degree the beyond reform-sphere of “different questions, with different, or no, answers” (Andreotti et al., 2015). This is perhaps most greatly emphasized when one group is asked directly “Do you guys feel you’re learning about this in school?” where the response was a resounding sarcastic “No.”

Discussion and implications

Returning to the initial research question on how Norwegian youth experience and reflect upon sustainability, the material shows that student participants display high awareness and at times complex reflections about sustainability, social justice, and the need for change. The workshops created a space for the students to critically reflect and discuss sustainability in ways they expressed that they were not used to doing. Based on arguments in earlier research on GCE and ESD that they do not highlight structural inequalities and social injustices, the students’ abilities to connect sustainability to these issues, was striking. Observations and conversations with the students showed a clear awareness that mainstream notions of progress and modernity have historically produced and resulted in the present predicament of unsustainability. Simultaneously, the students also expressed the need for more and better tools to imagine and explore alternatives, and a frustration that their current education is not providing them with these tools. Many of the students struggled to grasp how present approaches within their curricula are sufficient to prepare them for an unknown future and enable change. The insights from our material reveal a clear desire among the students for more critical conversations on these issues. The students refer to critical thinking and problem solving and, directly and indirectly, express that present curricular approaches do not suffice. The workshops opened the space for “social learning,” as described by Ojala (2015), “on the level of deconstruction, looking inwards, confrontation, listening to others, and reconstruction, creating new perspectives, insights”(Roberts, 2022, p. 83). Our analyses of the conversations as well as the students’ own comments, point towards the need for a more in-depth understanding of coloniality and the challenges of epistemological universalism.

Although the workshops opened a space for a type of criticality the students were not used to, yet strongly appreciated, they did not seem to have the conceptual tools to articulate fully their criticality. As argued by Andreotti et al. (2015), the radical reform-space is recognized by resisting modern/colonial epistemological dominance. This sphere of criticality allows for “the recognition of how unequal relations of knowledge production result in a severely uneven distribution of resources, labor, and symbolic value” (Andreotti et al. 2015, p. 26). By engaging with more diverse approaches to knowledge and being provided with frameworks to question western universality, students could be offered more pluralistic ways of imagining and understanding relations to and with land/nature/one another (cf. Karsgaard & Davidson, 2023). Although students were aware of alternative epistemologies such as Indigenous knowledges, it is important to emphasize that these were relegated to the sphere of “pre-historical,” and clearly demonstrated a movement towards a deeper understanding of how mainstream approaches to sustainability negate marginalized perspectives. The data reveals the need for more explicit and in-depth knowledge, and validation, of Indigenous and marginalized knowledges and perspectives in education. Something, we concede, could also have been better included in the workshop design.

While the provision of more accurate knowledge and epistemological diversity should be a main task of education, we agree with Andreotti et al. (2015) that global social injustice and climate change cannot be solved with the commonly suggested remedy of “more knowledge” and “better analyses” alone (Andreotti et al., 2015, p. 36). Our material also suggests that deeper change is needed, related to a redefinition of education such that it corresponds with the beyond reform-sphere: asking different questions and providing different answers. The level of criticality and capability to ask questions and problematize the current status quo displayed by the students shows that achieving this is not only about students’ relative lack of abilities or competencies, but rather about creating spaces for these kinds of conversations in education.

There is a clear ambivalence in students’ perspectives between an explicit disbelief that education can provide the competencies they need, and a lingering hope that education can still be a pathway towards empowerment, change and sustainability. This ambivalence is expressed by Unit2BS1, who describes education as being there “To uphold the power structure… That’s what it is about.” This statement resonates perfectly with academic critiques of education as being embedded in the high values of social justice and sustainability, but the implementation of such efforts remains entrenched in the reproduction of the CMP through its focus on market rationality and nation state competitiveness, reproducing current global power structures.

With Ojala (2017), we uphold that the sense of disillusion expressed by many of the students should be met with critical hope in and through their education, and that this hope must also be informed and realistic (Eriksen & Jore, 2023). As argued by Biswas and Mattheis (2022), who write about youths’ climate change activism, such initiatives enable prefigurative social practices that make possible the imagination of alternative social realities. They uphold that education may learn from such youth initiatives, pointing towards a childist reform of education where children are also seen as potential teachers. Such activism is recognized by engaging more levels of experience than the cognitive, including: affective, embodied, and emotional knowledges and practices. As the students suggest themselves, we argue that the fine balance between providing accurate and critical knowledge about the world, without robbing students of hope, can be navigated with more creative and imaginative pedagogies. There is a strong sense from all the students that more creative and action-oriented approaches are needed and wanted. Space must be given to ask questions even if they cannot be answered; to ask different questions and imagine different answers, in other words move beyond reform (Andreotti et al., 2015). Enabling such creative, open-ended, and imaginative learning processes also implies a more radical recognition of the students themselves as knowledge producers.

References

- Abebe, T. & Biswas, T. (2021). Rights in education: Outlines for a decolonial, childist reimagination of the future–commentary to Ansell and colleagues. Fennia-International Journal of Geography, 199(1), 118–128.

- Andreotti, V. D. O. (2015). Global citizenship education otherwise: Pedagogical and theoretical insights. In A. Abdi, L. Shultz, & T. Pillay (Eds.), Decolonizing global citizenship education (pp. 221–229). Brill.

- Andreotti, V. (2016). The educational challenges of imagining the world differently. Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue canadienne d’études du développement, 37(1), 101–112.

- Andreotti, V., Stein, S., Ahenakew, C., & Hunt, D. (2015). Mapping interpretations of decolonization in the context of higher education. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 4(1).

- Andreotti, V., Stein, S., Sutherland, A., Pashby, K., Susa, R. & Amsler, S. (2018). Mobilising different conversations about global justice in education: Toward alternative futures in uncertain times. Policy & Practice, 26, 9–41.

- Biswas, T., & Mattheis, N. (2022). Strikingly educational: A childist perspective on children’s civil disobedience for climate justice. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 54(2), 145–157.

- Bragdø, M. B. (2022). Education for sustainable development in social studies: A scoping review of results from Scandinavian educational research. Nordidactica: Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education, 12(4).

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

- Christie-Blick, K. (2021). Climate justice: Science for a better world. The Science Teacher, 89(1), 20–26.

- Cortina, R., Martin Alcoff, L., Green Stocel, A., & Esteva, G. (2019). Decolonial trends in higher education: Voices from Latin America. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 49(3), 489–506.

- Darder, A. (2020). Teaching as an act of love: Reflections on Paulo Freire and his contributions to our lives and our work. Επιστήμες Αγωγής, 2020, 177–190.

- Elkorghli, E. A. B. (2021). The impact of neoliberal globalisation on (global) citizenship teacher education in Norway. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 19(5), 610–624.

- Eriksen, K. (2018). Education for sustainable development and narratives of Nordic exceptionalism: The contributions of decolonialism. Nordidactica: Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education, (4), 21–42.

- Eriksen, K. (2021). “We usually don’t talk that way about Europe…” Interrupting the coloniality of Norwegian citizenship education Doctoral dissertation [University of South-Eastern Norway].

- Eriksen, K., & Jore, M. K. (2023). (Tapte) muligheter for kritisk tenkning: Post- og dekoloniale perspektiver i samfunnsfag [(Lost] Opportunities for critical thinking: Post- and decolonial perspectives in social studies]. Nordidactica: Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education, 13(2), 135–158.

- Eriksen, K. G., & Svendsen, S. H. B. (2020). Decolonial options in education–interrupting coloniality and inviting alternative conversations. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education, 4(1), 1–9.

- Fjellheim, E. M. (2023). “You can kill us with dialogue:” Critical perspectives on wind energy development in a Nordic-Saami green colonial context. Human Rights Review, 24(1), 25–51.

- Freire, P. (2018). Teachers as cultural workers: Letters to those who dare teach. Routledge.

- Harper, D. (2002). Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies, 17(1), 13–26.

- Huckle, J., & Wals, A. E. (2015). The UN decade of education for sustainable development: Business as usual in the end. Environmental Education Research, 21(3), 491–505.

- Karsgaard, C., & Davidson, D. (2023). Must we wait for youth to speak out before we listen? International youth perspectives and climate change education. Educational Review, 75(1), 74–92.

- Keskinen, S., Skaptadóttir, U. D., & Toivanen, M. (2019). Undoing homogeneity in the Nordic region: Migration, difference and the politics of solidarity. Taylor & Francis.

- Kincheloe, J. L., McLaren, P., Steinberg, S. R., & Monzó, L. (2018). Critical pedagogy and qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research 5th ed., (pp. 235–260). Sage Publications.

- Knutsson, B. (2018). Green machines? Destabilizing discourse in technology education for sustainable development. Critical Education, 9(3).

- Kvamme, O. A., Sæther, E., & Ødegaard, M. (2019). Bærekraftdidaktikk som forskningsfelt. Acta Didactica Norge, 13(2).

- Mignolo, W. D. (2007). Delinking: The rhetoric of modernity, the logic of coloniality and the grammar of de-coloniality. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), 449–514.

- Mikander, P. (2015). Colonialist “discoveries” in Finnish school textbooks. Nordidactica: Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education, (4), 48–65.

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), Article 1609406917733847.

- Ojala, M. (2017). Hope and anticipation in education for a sustainable future. Futures, 94, 76–84.

- Pashby, K., da Costa, M., Stein, S., & Andreotti, V. (2020). A meta-review of typologies of global citizenship education. Comparative Education, 56(2), 144–164.

- Pashby, K., & Sund, L. (2019). Teaching for sustainable development through ethical global issues pedagogy: A resource for secondary teachers. Manchester Metropolitan University.

- Pashby, K., & Sund, L. (2020a). Decolonial options and challenges for ethical global issues pedagogy in northern Europe secondary classrooms. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education, 4(1), 66–83.

- Pashby, K., & Sund, L. (2020b). Decolonial options and foreclosures for global citizenship education and education for sustainable development. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education, 4(1), 66–83.

- Pihkala, P. (2020). Eco-anxiety and environmental education. Sustainability, 12(23), Article 10149.

- Pirbhai-Illich, F., Osber, D., Martin, F., Chave, S., Sabbah, M., & Griffiths, H. (2017). Decolonizing teacher education: Re-thinking the educational relationship research seminar report. Canada-UK Foundation.

- Roberts, B. A. (2022). A whole story perspective: Norwegain youth reflections on Sustainable Development Goal 4.7. Norwegian University of Life Sciences.

- Sinnes, A. T., & Straume, I. (2017). Bærekraftig utvikling, tverrfaglighet og dybdelæring: Fra big ideas til store spørsmål [Sustainable development, interdisciplinarity and deep learning: From big ideas to big questions]. Acta Didactica Norge, 11(3).

- Stein, S., Andreotti, V., Suša, R., Ahenakew, C., & Čajková, T. (2022). From “education for sustainable development” to “education for the end of the world as we know it”. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 54(3), 274–287.

- Sund, L., & Pashby, K. (2020). Delinking global issues in northern Europe classrooms. The Journal of Environmental Education, 51(2), 156–170.

- Tiostanova, M. V., & Mignolo, W. (2012). Learning to unlearn: Decolonial reflections from Eurasia and the Americas. The Ohio State University Press.

- UDIR. (n.d.a). Core curriculum Interdisciplinary topics. https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/prinsipper-for-laring-utvikling-og-danning/tverrfaglige-temaer/?lang=eng

- UNESCO. (2020). Education for sustainable development: A road map. https://doi.org/10.54675/YFRE1448

- Zavala, M. (2016). Decolonial methodologies in education. In M. A. Peters (Ed.), Encyclopedia of educational philosophy and theory (pp. 1–6). Springer.

Footnotes

- 1 Also known as the Incheon Declaration.

- 2 HEADSUP is an acronym that stands for Hegemony, Ethnocentrism, Ahistorism, Depoliticization, Self-congratulatory, Uncomplicated solutions and Paternalism (Andreotti, 2016).

- 3 Participating schools are represented as Unit 1, 2 and 3 and subdivided into smaller groups which are identified as Unit1A, Unit1B etc. and speaker as S e.g., Unit1BS1.