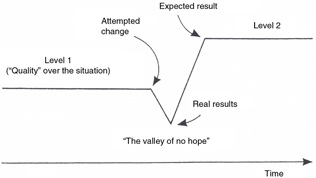

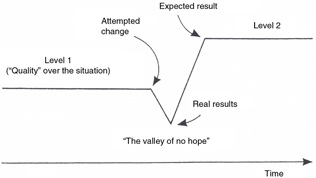

Figure 1. “The valley of no hope - syndrome” is typical in many organizational reforms (Albrecht, 1985).

Peer-reviewed article

Hans Petter Saxi*

Nord University, Bodø, Norway

Abstract

Amalgamating public organizations is one of the most used strategies for improving welfare production in the Western world. This is also the case for the school sector in Norway. The reformers expect that merging units will facilitate scale advantages, thus leading to reduced overhead costs and increased specialization. However, these expectations are often dashed by evaluation studies. This gap between the great expectations held by reformers and the evidence collected by evaluators can be explained by using evaluation methodology. Implementation of organizational reforms takes time, and too often evaluations are conducted too early after implementation has taken place. This article is based on a longitudinal study of amalgamating three upper-secondary schools in Norway based on three evaluations conducted 2, 6 and 17 years after implementation. The study demonstrates that the perceived effects of the amalgamation of upper-secondary schools can change dramatically during the course of time. One conclusion is that longitudinal studies do have methodological limitations, but they should still be conducted more often in evaluation research.

Keywords: Long-term evaluation; methodology; the merging of schools

Received: December 2015; Accepted: November 2016; Published: February 2017

*Correspondence: Hans Petter Saxi, Nord University, 8049 Bodø, Norway, Email: Hans.p.saxi@nord.no

©2017 Hans Petter Saxi. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Citation: Hans Petter Saxi. “Long-term effects of amalgamating of upper secondary schools. A contribution to evaluation methodology.” Nordisk tidsskrift for pedagogikk og kritikk, Vol. 3, 2017, pp. 1–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.23865/ntpk.v3.244

In our time, “big is beautiful” and the amalgamation of organizations have become a popularly used recipe for handling organizational problems. This has been the case in most of the Western world since The Second World War. Norway, which is the focus of this article, is a good case in point: the program theory leads on the hope of improving organizations through amalgamating various units. By amalgamating organizations in the welfare state, reformers aim to gain economies of scale, advantages then fronted by slogans such as “more welfare for money”. Several reasons exist for this hope. Large units are expected to reduce overhead costs involving reduction of leadership, accounting departments, procurement offices, etc. One also expects larger units to enable a greater degree of specialization. A third expectation is that amalgamating organizations will provide an increase in resources, which in turn can provide the amalgamated unit with a greater capacity for self-determination.

However, evaluation studies carried out on amalgamating organizations in the public sector in Norway show that these reforms have in fact not proved successful. One recent example showing this is the NAV-reform; this is the biggest amalgamation ever carried out in the public sector in Norway since the establishment of the welfare state in the country. So far, evaluations show that the improvements expected of this reform have not been realized, and the reform processes have produced significant side-effects such as a more centralized system at the expense of local autonomy (Andreassen & Fossestø, 2011; Fimreite & Aars, 2011). Another example is the amalgamation of Oslo’s hospitals in 2009. This reforming process was characterized as moving from “crisis to crisis” with massive critique from the employees (Andersen, 2012; Slagstad, 2012). A third contemporary example comes from the university sector where a previous total of 14 universities and university colleges have now been reduced to just five after mergers. Some of these mergers have involved significant resistance from employees. These examples of contemporary big mergers have their own specific dynamics and their relevance for the selected case in this article, which is one amalgamation process of upper secondary schools, is not obvious.

At upper secondary education level, amalgamating schools is a popular reform strategy in Norway (Kleivan & Nilsen, 2008; Skattum, 2009; Saxi, 2014). This article is built on a longitudinal case study of the effects of amalgamating three secondary schools in the municipality of Fauske in the county of Nordland. The amalgamation was implemented in 1994, and has since then been evaluated three times. The first evaluation was carried out in 1996 (Saxi, 1996), the second in 2001 (Berg, Kvig & Slottholm, 2002; Saxi, 2001), and the last in 2011, 17 years after implementation. The first evaluation built on personal interviews, questionnaires, and “essays” written about the amalgamation process, which made “triangulating” possible (Saxi, 1996, p. 3–9). The two follow-up evaluations were built purely on questionnaires. The first study concluded that the effects were “upsettingly negative”. The second evaluation showed results that were more neutral. The last study the impacts were assessed as being very positive. The three evaluations showed a dramatic shift in opinions on the part of the employees in relation to the amalgamated unit. The longitudinal design reveals that the timing of the evaluation studies can be of crucial importance for what we actually find.

Several social scientists have commented on evaluations being carried out too early after the implementation of reforms (Kautto & Similä, 2005; Kirst & Jung, 1982; Pressman & Wildawsky, 1984; Putnam, 1993; Sverdrup, 2003). However, very few evaluation studies are in fact designed to allow for the impact of time. The reason for this is mainly that the people commissioning evaluation studies in the public sector are politicians and administrative leaders, who are subject to time pressure and have to demonstrate the effects of their policy. This explains the paradox that great expectations to amalgamation are dashed in many evaluation studies – because the studies are carried out too soon. This article provides a contribution to evaluation methodology, with the aim being to demonstrate the advantages and problems of a longitudinal design in evaluation studies.

Since the 1960s, there has been a significant growth in the number of young people taking upper secondary education in Norway as well as the number of secondary schools. The 19 counties are the owners of the upper secondary schools. In the county of Nordland, the number of these schools was 37 in the 1990s, before the county council decided to start the process of amalgamating them. Today the total number of upper secondary schools in the county of Nordland has been reduced to 19. Fauske upper-secondary school was the first to be amalgamated in 1994.

The three upper secondary schools in Fauske were quite different from one another. One of the schools specialized in educating pupils to take university studies, another specialized in health care and social education programs, and the third specialized in vocational studies such as driving heavy vehicles and machines, etc. The amalgamation of these three schools was met with great expectations from the elected representatives of Nordland County Council and the county administration. It is therefore possible to treat the amalgamated upper secondary school in Fauske as a critical case. If the amalgamating process did not succeed here, there was no use trying the amalgamating strategy elsewhere where conditions were not as promising. However, the locals had more mixed expectations. On the one hand, they hoped a new school would be built as part of the package. On the other hand, they were also skeptical to rationalization of the school system.

The overall conclusion in the first evaluation report was that amalgamating the three secondary schools in Fauske resulted in “upsettingly negative effects” (Saxi, 1996, p. 21). The great majority of the employees at the schools reported in questionnaires and in personal interviews that the effects were negative. As many as 66 percent of the employees reported “bad experience” or “very bad experience” with the reform, as we can see in Table 1. Just 4 percent reported “good experience” and none had “very good experience”. The employees did not find that the aims for the amalgamating process had been fulfilled. Moreover, many negative side effects were reported. Nine out of ten employees mentioned, for example, that the level of conflicts had increased at their workplace.

Why did the amalgamating process fail so badly? From the literature concerning organizational reforms we are aware of many reasons for failure (March & Olsen, 1989; Pressman & Wildavsky, 1984). In the case of amalgamating the upper secondary schools in Fauske several factors contributed to the outcome. Broadly, these factors can be named as deviations from a rational reform strategy characterized by the following steps: 1) discovering and diagnosing the problem, 2) selection for the treatment, 3) implementation of the treatment, and 4) a systematic evaluation process to evaluate and modify process if progress not achieved.

One common failure in reform processes is that reformers start with solutions not with problems (March & Olsen, 1989). This deviation has significance for the case at hand. The initiative for the reform came from the county administration and was confirmed by the county council. It did not originate from the local headmasters or teachers. The locals had an ambivalent attitude to this merger initiative. They interpreted the initiative to amalgamate the schools as an order. In addition, they wanted to have a new building for the upper secondary school in Fauske, which they were promised if they accepted the merging of the schools. On the other hand, they had second thoughts regarding this initiative which they interpreted as a solution to problems in the county administration, not in Fauske.

Another deviation from the rationalistic ideal was the lack of selection and priority of aims in the case of amalgamating the upper secondary schools in Fauske. This is a common reason for failures in organizational reforms. The reformers try to fulfill too many aims at the same time, and there is hardly any limit to the positive expectations of many organizational reforms. It is also commonly the case that many of the aims actually conflict with one another. This was indeed the case for the goals in the merging process in the upper secondary schools in Fauske. The reformers aimed for improvements in resource allocation, financial savings, more spending available for education, better coordination between the schools, increased autonomy for the school, development of a uniform set of values, and even increased job security for the teachers. The aims were not given priority in relation to one another and some of them actually conflicted with one another. For instance, increased job security and expected financial savings on the budget.

The third deviation from the rational reform ideal was the serious lack of capacity and focus on the implementation process when amalgamating the upper-secondary schools in Fauske. Re-organization normally requires an increase in working hours while “the ship has to be re-built on the high seas”. This leads to the paradox that reforms aimed at saving resources in the long-run require more resources in the short-run. To smooth out the amalgamation process, the county council gave the new amalgamated school in Fauske the same budgetary framework as the three schools in Fauske had together been previously allocated. In addition, a new headmaster for the amalgamated upper-secondary school in Fauske was put in charge half a year before the amalgamation of the three schools actually began to take place. Despite these conditions, the reforming process was characterized by the employees as “unclear, and with too many loose ends”. This ended up in a lot of meetings and extra work. One reason for these problems with capacity and focus in the implementation process was that it was implemented simultaneously with Reform 94, a radical change in the organization of upper secondary schools in Norway. As if this was not enough, a new IT solution and accounting system were both implemented during the same year. This added to the problems of insecurity and instability.

These implementation problems in amalgamating the upper secondary schools in Fauske facilitated conflicts. The literature regarding organizational development is amply equipped with examples of this (Hansen & Vedung, 2010; Moe, 1989). Organizational conflicts in relation to amalgamation can have many sources, but two reasons stand out: conflict of interests and cultural conflicts. Amalgamating organizations can lead to conflicts of interests in that the systems of power, resources and prestige have to be re-distributed. An organization normally represents a stable distribution of power and other sets of resources (Pfeffer, 1993). Reforms disturbing this equilibrium will be met with friction from those expecting to lose resources, and support from persons expecting to gain from the reforms. Conflicting interests were reported in the newly merged upper-secondary school in Fauske by an increase in conflicts in the budgeting process. The second source of conflicts arises from deep-rooted values amongst organizational members. When organizations are merged, the members of the former organizations have to interact on a more regular basis, and this can result in cultural conflicts. The teachers on the study programs leading to university competence were for example in principle against big units. They argued in favor of small schools in which governance is easier with shorter communication lines between the headmaster, the teachers and the pupils. The more unequal the cultures in the merging organizations are, the higher the chances are of such value conflicts.

An illustration of cultural differences was revealed by the reaction between the three amalgamated schools towards the meetings at which the preliminary results from the evaluation report were presented. The teachers at the school preparing pupils for university studies criticized the headmaster for being autocratic. They wanted more cooperation and information. The teachers of vocational studies were also critical, but their critique was of the opposite kind. For them the meetings were a waste of time. They wanted the headmaster to be more clear and efficient. The teachers at the department providing health care and social programs did not wish to face the headmaster at all. Before attending the meeting, they demanded that the headmaster should be absent. These demands were met and at the meeting, the teachers presented a picture of the headmaster as an autocrat. These differences in the perception of the headmaster illustrate the cultural division and contradictory expectations from the teachers at the former schools. This also shows clearly that mergers can facilitate severe challenges for the leaders.

Two years after implementing amalgamation of the upper secondary schools in Fauske, hoped-for achievements had clearly not been met. The merging of the schools was intended to act as a trial case, and the evaluation report was meant to tell the reformer whether or not amalgamating was a fruitful strategy for other upper secondary schools in the county of Nordland. Much attention was therefore paid to the report. Based on the negative conclusions, one could have expected that the amalgamation process in Fauske would be reversed, and that the school would be split up again into its three former units. This did not prove the case, however, and the amalgamated upper-secondary school in Fauske continued as a unit. In addition, school amalgamation was introduced in several other municipalities in the county of Nordland, and the evaluation report disappeared into the archives of the county administration.

The decision to continue with the amalgamated upper-secondary schools in Fauske facilitated a longitudinal evaluation. Two follow-up studies were conducted: one in 2001 by a group of students on a course in the management of schools (Skoleledelse) (Berg et al., 2001; Saxi 2002) the other was conducted in 2011 by the present author, 17 years after implementation in 1994. Both of these studies were based on the same designs as the first evaluation, but they were simplified and concentrated on questionnaires. In the following table, we can see the development in opinions regarding a key question over a period of time.

Table 1 clearly shows that there has been a radical shift in the employees’ opinion at the amalgamated secondary school at Fauske from being very negative in 1996, to more neutral in 2001, and finally to being very positive in the last evaluation in 2011. In 1996 as many as 66 percent of the staff reported either bad or very bad experience of the amalgamation of the schools. This proportion was reduced to 16 percent in 2001, and further to just one percent in 2011. This indicates that the timing of the evaluation is of great importance. In the case in hand, the early and the late evaluations portrayed completely different pictures of the effects of the amalgamation of the upper secondary schools in Fauske. One advantage with longitudinal design is that we become aware of these changes over time. The County Head of Education replaced the Headmaster of the amalgamated upper secondary schools in Fauske after the first evaluation had been carried out. This can be interpreted as actually forming part of the implementation of the amalgamating process. Interpreted in this way, the implementation and the evaluation of the amalgamating process were integrated into one another and it is not easy to set a clear-cut starting and ending point for the two processes. In such situations, a longitudinal design is to be preferred, because it highlights the processual aspects of implementations of reforms.

How then can we explain these radical shifts in the opinions, over a period of time, amongst employees in the upper-secondary school in Fauske? One explanation can be found in a model called “the valley of no hope”.

It is a paradox that the theoretical expectations related to reforms in organizations can be very well-founded, but that evaluation studies reveal that the effects are negative, as indeed demonstrated in many evaluation studies. At least a part of this paradox concerns the methodology of evaluation. Because evaluations are normally conducted too soon after the implementation of a reform, when actors are still struggling to adapt to the innovation, the short-term effects can be very negative. This does not, however, alter the expected positive outcomes in the long run. Longitudinal studies represent a key to understanding the gap between the reformers’ optimism and the negative findings revealed in evaluation research.

Figure 1, which the organizational consultant Karl Albrecht (1983) has named “the valley of no hope”, aptly illustrates these points. When comprehensive reforms are implemented in an organization, this affects the basic routines which become “melted up”. If the actors face problems with implementation of the new system being used to replace the old system, this can produce frustration amongst the staff. This phase in an implementation process also requires a lot of meetings and paperwork both for leaders and for employees. Especially for leaders, organizational reforms are demanding, and during the reform period the “nine to five” style of work often proves insufficient to handle the problems. The demands from the surrounding world have to be met simultaneously with implementation of the new routines. When such situations last over time, this can result in frustrations and conflicts and bring the organization “over the cliff-edge”, as illustrated in the figure. This will bring the organization further away from the expected and desired situation actually intended by the reformers. In such a frustrating situation, the reformers in charge of the reform can face tension and criticism from the employees and this may deplete the process even further. The organization may then face a temporarily chaotic situation, which can in turn bring the organization into “the valley of no hope”, as illustrated in Figure 1. If a “thermometer” is dipped into the reform process at this stage, the measurement can deviate radically from the measurement of the normal situation before implementation of the reform, and even more so in relation to the expected outcomes.

Figure 1.

“The valley of no hope - syndrome” is typical in many organizational reforms (Albrecht, 1985).

Depending on local conditions and how comprehensive the reform is, “the valley of no hope” can be deep or shallow, long-lasting, or short-lived. After awhile, if the new routines get on track, and tensions and conflicts calm down, the members of the organization can experience positive development. If expectations have been fairly realistic, the situation becomes more normalized and realization of the aims can then be fulfilled. The source of this realization can be based on experience with improvements in the new model. It can also be a result of institutionalization. The new structure becomes infused with value, and over time becomes taken for granted (Selznick, 1984). This being said, it is also perfectly possible that the new equilibrium can prove to be even worse than the situation was before the reform.

Some obvious methodological comments have to be made concerning Table 1. As we can see, the percentage of the employees answering the questionnaires dropped from 88 in 1996, to 80 in 2001, and further down to 54 percent in 2011. This indicates that the relevance of the evaluation faded over time. One reason for this is that it was hard for some of the employees in the last evaluation to remember what happened almost two decades earlier. The other reason is that many new staff members were appointed after the implementation of the reform. These new staff members had no knowledge of the amalgamation process. These factors clearly limit the validity of longitudinal studies. In addition to these problems concerning measurements in longitudinal studies, some other fundamental problems and advantages in relation to longitudinal design of evaluations of organizational reforms need to be handled more in detail.

The first problem concerns the lack of “objective” data, and can have many sources. Reformers commissioning an evaluation rarely consider evaluation design when implementing reforms and wanting to have these reforms evaluated. In the case of the amalgamation of the upper secondary schools in Fauske, the evaluation study was commissioned after implementation had taken place. This eliminated the possibility of conducting a before and after type of design, and it was not possible to conduct a comparison in which we could have analyzed a possible gap in output between the three former schools and the amalgamated one. Another reason for the lack of objective data was caused by changes in accounting routines related to the new data package introduced shortly after implementation of the reform. This eliminated the possibility of measuring the economic impacts of amalgamating the schools. Because of this, the evaluation had to be based on questionnaires, personal interviews of key informants, and “essays” about the reform process written by 20 of the most affected leaders, employees and union leaders. Instead of measuring objective impacts, the evaluation had to rely on the perceived effects of the amalgamation reform as seen by teachers and administrative staff. Evaluations then take the form of being an opinion poll. This is not a problem exclusively for longitudinal studies, but these studies enabled us to discover that perceived effects can vary considerably over time.

The second problem arises from the fact that implementation of the reform ended up in conflicts. This is quite normal in cases of amalgamating organizations, as mentioned previously. Evaluators very often find that evaluations are part of a political game (Hansen & Vedung, 2010). This especially creates a disturbing problem in cases where we lack “objective” measurements of impacts. In such cases, the evaluator has to rely on statements from persons affected by the reform. Whether this is in the form of qualitative interviews or quantitative questionnaires, the problem is that the informants can present the effects of the reform in such a way that their own interests and values are favored. The persons gaining from the reform will have a tendency to present a overly postive picture of the effects, whereas the persons who interpret the reform as a process in which they lose resources, will have a tendency to paint an overly negative picture. Evaluators have to be aware of this possibility, and have therefore to remain somewhat “suspicious” of informants. Especially in cases where conflicts exist, this interpretative “suspiciousness” needs to be kept in mind. To treat the information presented from the actors as purely plain facts can trap the evaluator into a naïve interpretation. In cases such as the amalgamation of the upper secondary schools in Fauske, where a conflict existed between the headmaster and the teachers, the overall picture was very negative and painted “in black”, simply because the teachers formed the majority of respondents to the questionnaires. Using the longitudinal design, we can see that the frustrations and conflicts disappear over time. Longitudinal designs enable us to discover whether these conflicts are facilitated by persons or by more fundamental structures. When these conflicts calmed down after the replacement of the headmaster, the explanation seems to lie in personal leadership, and not fundamental structural factors. Using a longitudinal design, we are able to provide answers to questions regarding which explanations are the most reliable.

A third problem in longitudinal evaluation of organizational reforms is connected to impacts from the surroundings of the organization. Organizations are open systems, and they cannot be isolated. In our time, for example, the waves of organizational reforms appear with high regularity, and it is hard to isolate the impact of one reform from another. For long-term evaluation studies trying to measure the effects of one particular reform, this represents a serious challenge. Reforms in organizations are therefore not scientific experiments. In natural science and laboratory experiments the scientist isolates the object or the process which is to be investigated. In the laboratory the scientist controls all the variables and manipulates the values of variables one at a time in order to measure their impacts. Such levels of isolation from the surroundings are impossible to ensure in real-life reforms in organizations. Generally speaking, we can say that the longer the duration of the reform process, the more impact the surroundings have, thus extending the identification problem over time. For instance, the impact of the reform in focus will fade when the effects of the new reforms start to have an impact. As we have seen in the case of the amalgamation of the upper secondary schools in Fauske, two other reforms were implemented during the very same year, indicating that this is also a problem for regular evaluation studies. However, the upper secondary school sector in Norway has been reformed several times since then, and it is obviously much more demanding to trace any impacts from the original reform as times goes by. In the Norwegian educational sector, the eagerness to reform during the last decades has been so great that this has been seen as a main factor for bringing in new problems. This went so far that the government in 2011 promised not to initiate new reforms in the school systems.

The fourth and last problem relates to the diversity of the poorly operationalized aims characterizing many organizational reforms. This is common in organizational reforms in public services characterized by a multitude of values, interests and considerations (March & Olsen, 1988, 1989). As mentioned previously, many aims existed for the amalgamation process in Fauske. For the evaluators, this generated a problem related to which aims were of the most importance and how these should be measured. Another question is related to the symbolic aspects of aims. Symbols, such as the flag for instance, appeal to our feelings. Because they lack substance, they can be interpreted in many ways, and can therefore appeal to many people, despite differences. Such is the case with many aims in reform processes as well. They can have a function as symbols more than as precise measurements of a desired future. Longitudinal design makes it easier to evaluate whether or not the aims have a symbolic nature, while the real aims in use can more easily be revealed over a period of time. This was the case with the amalgamating process in Fauske, where a gap existed between the expressed values and the aims in the white papers from the county administration, and the real ones used in practice.

One overall conclusion of this longitudinal evaluation is that we need time to implement reforms. “Those who build new institutions and those who would evaluate them need patience” (Putnam, 1993, p. 60). The more comprehensive the reform, the longer the time period we can expect for implementation. However, the aim of the evaluation are of importance. On the one hand, if the aims are to evaluate the reform process, and not the outcomes, we need early evaluations in which the focus is on process. On the other hand, if the aims are to measure outcomes or effects, we need patience. Today, sitting with the answers about how the amalgamating process ended up in Fauske, one conclusion is that the reformers did succeed in the long run, despite the lack of goal achievement and the negative side-effects registered in the first evaluation. The legitimacy of today’s amalgamated upper-secondary school in Fauske is no longer questioned, and enjoys support from the great majority of its employees. This is good news for all the contemporary leaders in the public sector who face tensions and conflicts in amalgamating processes. The longitudinal study of the amalgamating process in Fauske clearly demonstrates that perceived effects can change dramatically over time, just like opinion polls. This indicates that the timing of evaluation is of crucial significance for measuring the effects. So when can we say that a reform has actually been implemented, and when is the right time to start the evaluation? There are no universal answers to this, but I would certainly recommend longitudinal studies as one solution to these questions aimed at measurement timing. Also single shot evaluations should be conducted after “the valley of no hope”, when the amalgamating is in the process of being institutionalized. Certainly, longitudinal studies require extra resources, and the persons funding the evaluation research are often in a hurry to get “the answers” and make the necessary improvements. Politicians have a limited period of time in power and have to show some results before the next election. These are the real-life conditions facing many evaluators.

A second conclusion to be drawn from the school amalgamation in Fauske concerns leadership. In comprehensive reform processes, the qualities of the leader do often make a difference. The capacity of both the leaders and the employees are scarce resources in times of significant organizational change. Because comprehensive reforms alter the established structures which are “melted down”, there will be periods of temporary chaos before the new structures “freeze” into routines once again. Another problem often arising in situations with a high level of ambiguity is tension and indeed conflicts. In relation to amalgamating organizations, different cultures and interests have to cooperate more intensively and this can provoke conflicts regarding values and resources. Leaders have to respond to these conflicts, either as parties to the conflict itself, or as negotiators. In either case this can involve personal strain in the form of critique and even “mudslinging”. In such situations the leaders’ skills are important, more so than in the more institutionalized periods of an organization’s life when habits and routines provide relief for members of the organization.

A last conclusion which can be drawn from the study presented in this article is that the evaluation process itself can also be a part of a game about power, money and honor. The stakeholders in the reform process may be interested in distorting the presentation of the outcomes of the reform if they expect to lose resources. This can certainly make it hard for the evaluator to present a truthful picture of the reform. In cases in which the evaluation totally or partially relies on the opinions of outcomes as seen by members of the organization, evaluation hardly differs from a regular opinion poll. In such situations, the employees represent the majority and will obviously carry more weight in the dataset than the leaders who are in the minority. The evaluation is then organized much like a numerical democracy, whereas organizations in normal conditions are hierarchies. If this hierarchy is built on legitimated processes, two forms of democracy are confronted. In the case of amalgamating the upper secondary schools in Fauske, it remains the case that the majority of the elected representatives in the county council decided to implement the reform. This democratically elected body is the principal and the administrative leaders are the agents. Interpreted in this way, representative democracy and majority at the workplace disagreed. In such situations, the representative democracy has priority. The ultimate principal for the public sector is made up of the citizens, who have selected their agents by way of election polls in a democratic process. This implies that cooperation from employees in reform processes is important, but has clear limitations in relation to political democracy. For evaluators this is important to bear in mind. Otherwise, evaluations can become a weapon for the interests of the employees in the public sector, thereby not representing the interests of the citizens concerned.

Hans Petter Saxi is Associate Professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Nord University. He has been doing research on political and administrative reforms in municipalities and counties in Norway, on regional development and resource management.

Albrecht, K. (1985). Organization development. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Andersen, B.M. (2012). ‘Lite lønnsom sykehusfusjon’.Sykepleien 7, 62–63.

Andreassen, T.A. & Fossestø, K. (2011). Nav ved et veiskille. Organisasjonsendring som velferdsreform. Oslo: Gyldendal.

Berg, B.V., Kvig, E. & Slåttholm, J. (2001). Ledelse i skoleverket. I hvilken grad har vi lykkes med å få til bedre samarbeid og ressursutnyttelse ved bruk av administrativ samordning?. Bodø: Prosjektoppgave. Høgskolen i Bodø.

Fimreite, A.L. & Aars, J. (2011). ‘NAV – forvaltningsreform for velferd’. Nordiske organisasjonsstudier 13(3), 3–8.

Hansen, M.B. & Vedung, E. (2010). ‘Theory-Based Stakeholder Evaluation’. American Journal of Evaluation, 31(3), 295–313.

Kautto, P. & Similä, J. (2005). ‘Recently Introduced Policy Instruments and Intervention Theories’. Evaluation, 11(1), 56–68.

Kirst, M. & Jung, R. (1982). ‘The utility of longitudinal approach in accessing implementation’. In W. Williams (Ed.), Studying Implementation. New Jersey: Chatham House Publishers.

Kleivan, B. & Nilsen, N.O. (2008). Fra 17 til 7 videregående skoler. Evaluering og veiledning av sammenslåingsprosesser i syv nordlandsregioner. Bodø: HBO-rapport 5.

March, J. & Olsen, J.P. (1988). ‘The Uncertainty of the past: Organizational Learning under Ambiguity’. I.J. March (Ed.), Decisions and organizations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

March, J. & Olsen, J.P. (1989). Rediscovering institutions. The organizational basis of politics. New York/London: The Free Press.

Moe, T. (1989). ‘The Politics of Bureaucratic Structure’. In J.E. Chubb & P.E. Peterson (Eds.), Can the government govern? Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

Pfeffer, J. (1993). Managing with power. Politics and influence in organizations. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Pressman, J. & Wildavsky, A. (1984). Implementation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Putnam, R.D. (1993). Making democracy work. Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Saxi, H.P. (1996). Hvorfor mislykkes reorganisering? Evaluering av forsøket med administrativ samordning av de videregående skolene på Fauske. Bodø: HBO-rapport nr. 4.

Saxi, H.P. (2001). ‘Stikk ikke målestaven ned i Håpløshetens dal!’ Utdanning 1.

Saxi, H.P. (2014). ‘Smått og godt, eller stort og flott? Langtidseffekter av fusjoner av offentlige etater’. In L.K. Monsen & J.B. Otterlei (Eds.), Valg, velferd og lokaldemokrati. Trondheim: Akademisk forlag.

Selznick, P. (1984). Leadership in organizations. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Skattum, C. (2009). Evaluering av 3 skolesammenslåinger i Buskerud. Oslo: Asplan Viak.

Slagstad, R. (2012). ‘Helsefeltets strateger’. Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening, 12(13), 1479–1485.

Sverdrup, S. (2003). ‘Towards an Evaluation of the Effects of Laws. Utilizing Time-series Data of Complaints’. Evaluation, 9(3), 325–339.