Introduction

School is where students spend most of their day and where they do most of their learning, playing and forming of relationships. Schools are thereby important settings for students’ academic, social and personal development (Anderman, 2002; Maddox & Prinz, 2003; Ravens-Sieberer, Freeman, Kokonyei, Thomas & Erhart, 2009). As a place where students face demands that may be experienced as either challenges or stressors, school can be not only a resource but also a risk to their academic success, subjective health and well-being (Løhre, Lydersen & Vatten, 2010a, 2010b; Samdal, 1998; Samdal, Nutbeam, Wold & Kannas, 1998; Samdal & Torsheim, 2012). The way in which students learn to manage school life may strongly influence their future health and well-being (Gustafsson et al., 2010).

I order to describe a student’s relationship with school, researchers have used different terms, such as “school engagement, school attachment, school bonding, school climate, school involvement, teacher support, and school connectedness” (Libbey, 2004, p. 274). The term “school connectedness” was used in the earliest large-scale study investigating this phenomenon, The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) in the USA (Resnick et al., 1997) and is the term used in this paper.

As research into school connectedness have been rooted in different disciplines, such as education, psychology, medicine and sociology, the concept lacked a clearly defined empirical base. To address this challenge, the conference on School Connectedness at the Wingspread Conference Center in 2003 aimed to identify existing research-based knowledge about school connectedness and to propose a set of core principles that would define the phenomenon (Blum, 2005). Researchers found, across this multidisciplinary field, three core characteristics to be important for the development of students’ sense of connectedness to school: safety, high academic standards and relationships. Safety included a physically and emotionally safe school environment; high academic standards were coupled with strong teacher support; and relationships were linked to an environment with positive and respectful relationships between students and adults (Wingspread Declaration, 2004). In academic research in the field, connectedness to school is often comprised of two components: one component characterized by commitment in the academic context and the other characterized by attachment engendered by relationships with people at school (Catalano, Haggerty, Oesterle, Flemming & Hawkins, 2004; Maddox & Prinz, 2003; Monahan, Oesterle & Hawkins, 2010).

Blum (2005) suggested that connectedness to school is about creating an environment that helps students trust that teachers care about their learning and about them as individuals. Teachers who have fair and consistent discipline policies, positive and proactive classroom management and the skills required to meet students’ developmental needs are in a position to increase students’ sense of being cared for. These teachers provide a healthy environment that may improve students’ health and well-being (Blum, 2005; Catalano et al., 2004; McNeely, Nonnemaker & Blum, 2002).

In fact, with regard to predicting good health and positive health behavior among young people, Blum and Rinehart (1997) considered connectedness to school to be the single most important aspect of the school setting. Further, the students’ school connectedness seems to have a great impact on academic motivation and engagement and thereby on increased learning outcomes (Juvonen, 2006; Libbey, 2004; McNeely & Falci, 2004). In addition to promoting better academic achievements and better health, connectedness to school may also serve as a protective element against a variety of health risk behaviors (Barber & Schluterman, 2008; Blum & Libbey, 2004; Bond et al., 2007; Maddox & Prinz, 2003). Thus, the students’ connectedness to school may act both as protection against risks and as a resource for learning, health and well-being. Researchers in the field of health promotion correspondingly value the learning environment and students’ relationship to school as factors that contribute to better health and educational outcomes (Leger, Kolbe, Lee, McCall & Young, 2007; Rowe, Stewart & Patterson, 2007; Samdal et al., 1998; Samdal & Torsheim, 2012). Research about promoting children’s mental health at school has also valued the significance of learning environments where students feel connected to a community of peers and where they are able to cope with their schoolwork and receive adequate support (Major et al., 2001).

As presented above, studies of school connectedness typically assess health, well-being or academic outcomes. In this study, outcomes were not our interest, as we wanted to elaborate the construct empirically. Bearing in mind the strong association of school connectedness with health, we considered it vital to investigate what contributes to school connectedness. Insights into what constitutes the construct of school connectedness may be helpful for individual teachers and for health promotion in schools. The aim of this study was therefore to explore how young students’ discussions about their learning environment and well-being reflected the construct of school connectedness.

Methods

In this study, we used existing qualitative data material gathered for exploration of what creates a healthy learning environment. A previous publication (Andersen, 2012) provides detailed information about methods. Here we give only a brief overview.

Design, participants and interviews

The researcher obtained consent from the school authorities, and parents returned a written, informed consent. The Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD) endorsed our study. The material was based on five focus group interviews with seventh graders from a primary school with approximately 500 students in an urban Norwegian municipality. Focus groups are typically considered an ideal way to explore experiences and obtain knowledge about a topic (Kitzinger, 1995). This method has also proven to be valuable when children are involved. However, in moderating focus groups with children, it is especially important to be aware of the imbalance of power between the adult and the young participants. The moderator therefore emphasized supporting participation of everyone in the group, as highlighted in the literature (Gibson, 2007; Morgan, Gibbs, Maxwell & Britten, 2002). The project leader (first author) asked teachers to create groups from the same class, consisting of girls and boys with different social and academic skills. Thus, the 31 participants, 11 girls and 20 boys, formed five groups. The participants are denoted Student 1 (S1), Student 2 (S2) and so on, and the focus groups are numbered Group 1–5, (G1–G5).

After welcoming the students, the interview session continued with open-ended questions supported by a semi-structured interview guide in order to let the discussion flow easily. Example questions include “When I say learning environment, what do you think about?” and “Does break-time have any impact on how you learn?” Guidance was kept to a minimum, and throughout the interview, the moderator continued to ask follow-up questions, e.g., “What’s needed for you to make an effort in school?”, “Do you know if the teacher supports you?” and “What is important for you in order to have a good time with your friends?”

Data analysis

The analysis followed the approach of theoretical reading, in which, according to Brinkmann & Kvale (2015), the researcher conducts a theoretically informed reading of the interviews rather than using specific tools or specific methods. This process involves movements from theory to data and back to theory. We found several excerpts leading to subthemes characteristic of school connectedness, as previously described in the research and the consensus document (Blum, 2005; Wingspread Declaration, 2004).

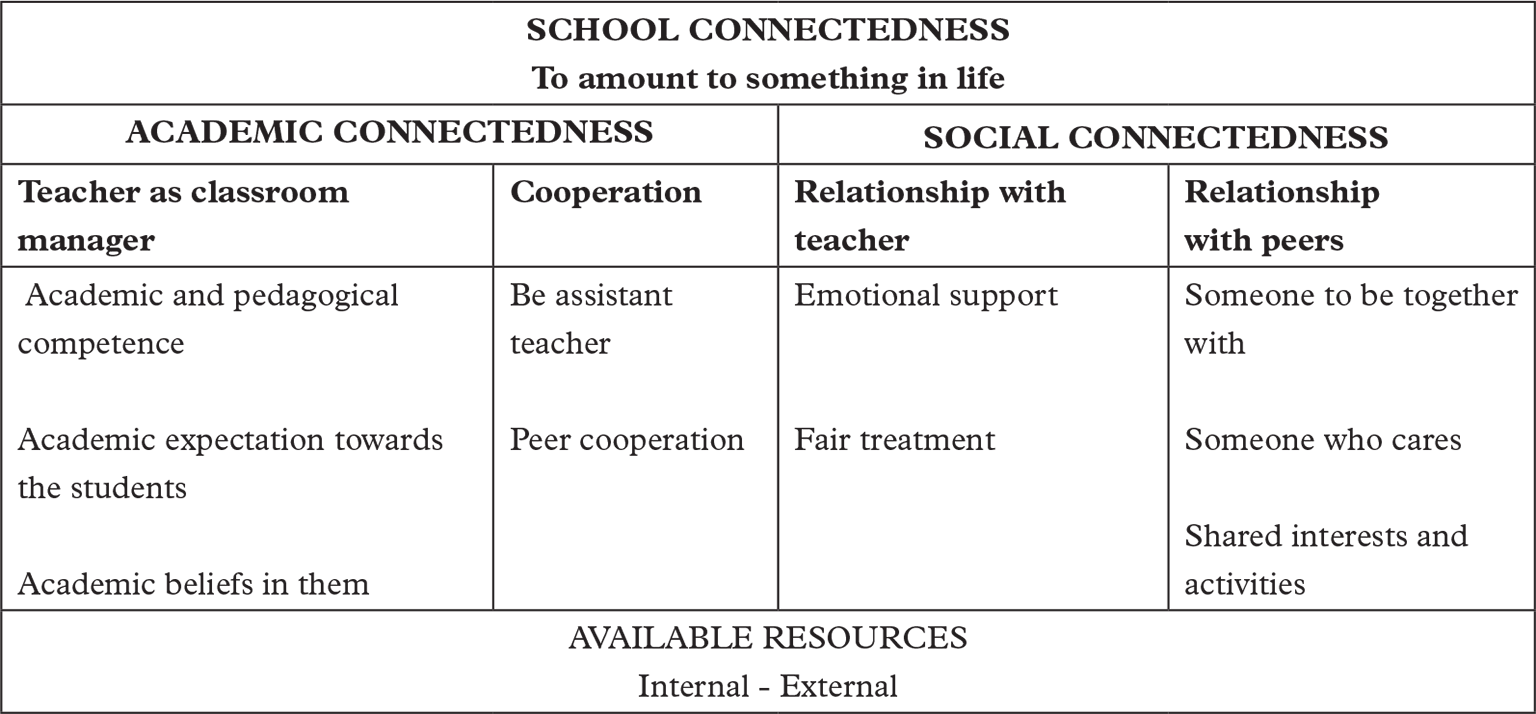

However, we also noticed that the material contained other excerpts of group communication that seemed highly relevant to the learning environment. We identified new themes pointing to the role of peers. Moreover, turning again to the literature of school connectedness, we realized that our analysis did not fit well with the often-used division between commitment and attachment (Catalano et al., 2004; Monahan, et al., 2010). Our analysis led to two components that we labelled “academic school connectedness” and “social school connectedness”; in both of these components, we found relational bonding and dedication to activities. The model of school connectedness is presented in figure 1.

Findings

Before we present the results, summarized in Fig. 1, we will first describe an overriding theme that emerged in all focus groups. It seemed to be important for students to experience school as meaningful, which they expressed through a strong wish “to amount to something in life”.

Meaningfulness – “To amount to something in life”

The students emphasized the meaning of going to school, and through almost every theme discussed, they mentioned the need for knowledge. Their wish to succeed and their longing to develop into competent adults was thus a recurrent theme throughout most of the topics in their dialogues. They focused regularly on their wish to amount to something in life. One of the students said: “I simply want to be successful and make something good out of my life. Be able to make a difference in other people’s lives” (S1). In their search for usefulness, it was important for them to understand why they had to learn what was taught to them, and they were concerned with how they could use this knowledge in the future: “We lose our motivation if we don’t understand the reason for learning something” (S2).

In the long run, their concerns were about academic achievement; they were concerned about their own futures in terms of getting a good education and having good job opportunities: “I look at school as a way of preparing for adulthood and getting a job” (S3). Additionally, when they talked about friends, the discussion was related to academic usefulness on several occasions. The students were concerned with how they could use each other as a resource to succeed. However, they also emphasized the social dimension, i.e. the importance of their relationships with friends. Break-time at school was here brought up as a key time for establishing friendships and connectedness, as shown in the citation below: “Enjoying recess helps us get along well at school” (S4).

The discussions primarily related to the students’ overriding theme of finding school meaningful and their wish “to amount to something in life”. The theme obviously had an academic dimension that constituted a driving force for the students. In this respect, the students’ relationships with their teacher and peers were of crucial importance, both academically and socially. This underpins the importance of experiencing connectedness to school.

Our data indicate that school connectedness is both about academic and social connectedness, with available resources as a fundamental prerequisite. An overall depiction of our themes and sub-themes is presented in Figure 1.

Academic connectedness

The analysis revealed a major theme identified as “academic connectedness”. It consisted of two sub-themes: Teacher as classroom manager and Cooperation.

Teacher as classroom manager

The data reveals that the teacher is essential to the students’ academic, social and emotional development. No matter what theme was discussed, the teacher was directly or indirectly a part of the students’ stories. The students were concerned with the teacher’s competence, not only academically but also pedagogically, in terms of communication skills and humour. They thought the teacher’s competence affected their ability to comprehend and learn, exemplified by the following conversation sequence:

I think we should have the very best qualified teachers … teachers who have a lot of education in the subject they are teaching (S3). Yeah, like in science. I didn’t use to like it, but then there was one teacher who made it fun (S5). Yeah, he was really a good science teacher (Others). (G1)

The students also highlighted the value of academic challenges, in terms of academic expectations from the teacher, to avoid boredom and lack of motivation. Students found it frustrating to be given tasks that were too easy or to be required to sit unproductively. The citation below shows both their wishes and their frustrations:

It would be more fun if the more advanced students could have a few more challenges, like getting assignments from junior high level (general agreement from others). Otherwise, we just sit there and get bored. Like when someone in class don’t know their mathematics and we do (S1). (G5)

Further, it was essential that the teacher functioned as a motivator, in terms of having beliefs in the students academically. We let a quotation by one student illustrate this: “If the teachers explain the assignment and then say that this is something we can manage, it isn’t so difficult. We try a little harder if they encourage us” (S5). Thus, academic challenges, coupled with teacher confidence, gave them the proper motivation to make an extra effort and gave them a sense that they could cope.

Cooperation

The students were eager to use their own competence to acquire more knowledge, and they wanted to be valued as highly competent. They emphasized that they liked to be an assistant teacher: “When the teacher lets you go around in the classroom helping others – kind of being a teacher – that makes you feel pretty good” (S2).

Several of the focus groups highlighted cooperation with classmates, showing the students’ desire to be part of the community. This focus on peer cooperation emerged under different themes and from different perspectives. The students found cooperation motivating, and they experienced better learning when they collaborated. Excerpts from different groups demonstrate this:

You get a lot of self-confidence and self-respect by helping others (S1, G5).

Because what you might not know someone else might know (S6, G3).

In a way, it helps if we can learn each other’s techniques (S18, G4).

The importance of learning to collaborate was often mentioned with an emphasis on future benefits, most notably job opportunities. We let one conversation sequence illustrate this:

We need to learn to work together (S8). Interviewer: How come? (Interviewer) You will need that skill in the future (S4). You have to learn to get along with others if you work in an office with other people (S12). (G2)

Social connectedness

In addition to being concerned with their academic performance, students were engaged in connecting with each other as well as with the teacher: “If you are in the same class for seven years and you know everyone, and your teacher is the same teacher, it makes you feel like you belong in that class” (S2).

Under the construct of “social connectedness”, we identified the following two categories: relationship with the teacher and relationship with peers.

Relationship with the teacher

The teacher was an actor in almost every story students told. Statements were enlivened with engagement and emotional assertions when it came to more relational themes. This was true of both positive and negative descriptions, especially when the students focused on their wish to be seen and heard by the teacher through positive feedback. Students talked about the significance of teachers who showed positive involvement and gave them emotional support, as illustrated in the following excerpts:

It’s really a lot of fun to get praise. Then you know when you have done something right or something well and that the teacher notices it (S1). It motivates us (S13). (G5) You feel so good when you get something right, and then, if the teacher says “good job”, that gives us more self-confidence and maybe makes us want to work harder (S7). It makes you happy (S16). (G3)

Regardless of the approach or theme discussed, much of what can be seen as unclear structures, expectations or consequences were described by the students as unfair. They wanted fair treatment from the teacher, with equal expectations and respect for all students, both academically and behaviourally. They were also concerned with predictability of the consequences linked to behavioural problems.

Teachers shouldn’t treat us differently. If there is someone who has problems, maybe they show them more respect and consideration than they do the rest of us (S13, G5).

A teacher should clamp down on those who really make noise and trouble (S11). There are a lot of teachers who don’t seem to care and don’t put a stop to it (S2). (G4)

As previously mentioned, the students were eager for knowledge. The focus of their concern was on their desire to have good working conditions at school. These discussions led to engagement and to many suggestions for how disturbing behaviour could be handled.

Relationships with peers

The importance of peer friendships were emphasized across themes and situations in many of the focus groups:

We have a kind of bond… (S6). Everybody in class is friends, in a way (S7). (G3)

We can help others when we are out at recess... that brings us closer together (S4, G2)

It was essential to have someone to be together with to avoid loneliness. An excerpt from one group illustrates this: “School is a place to make new friends (S15). Interviewer: Are friends important? (Interviewer) Yes (Others)! You can feel a little lonely if you don’t have friends” (S14). (G5)

Further, the students underlined the necessity of having someone who cares. Classroom peers were described as friends with whom the students felt connected. When the students had social or emotional problems, they saw each other as resources, and it seems that they were aware of the importance of social situations. The data showed quite consistently that the students primarily relied on their relationships with friends more than their relationships with their teacher.

We aren’t best friends with everybody in the class, but … we still keep an eye out for one another, if you know what I mean (S10). I usually look for my friends (S9). They help you if you are sad and comfort you (S16). (G3)

Moreover, the students highlighted that shared interests and activities were gateways to friendship. “It’s important to have something in common. If you are friends with somebody who also plays soccer and you’re on the same team, you can become better friends” (S7). In addition to break-time and leisure time, cooperation was mentioned as important, not only as a way of developing knowledge but also as a way of connecting with their peers and feel useful.

You talk more when you work together (S8). … but we still get the work done (S4). (G2)

You can talk and discuss things together (S17). And maybe you get a chance to help somebody ... that makes you feel a little better, in a way. Helping others is a good thing (S2). (G4)

Available resources

Students will inevitably have to handle the pressure of facing academic challenges in school. The students in this study showed awareness of available resources, both individual and external, and they used these when needed. As an individual resource, they pointed to their mental attitude and interest in a subject. Attitudes and interests seemed to be prerequisites for them to do their best and thereby benefit from mastery experiences: “First of all, I have to like the subject ... that makes me want to work harder. It has to be a subject I like before I try to do my best” (S4). It is possible that the students’ individual resources combined with academic challenges generated engagement, as expressed here:

Whenever I study hard for a test, I always feel confident that I will do all right (S6, G3).

Interviewer: What does it take to want to do well? (Interviewer) That you can do it and be better at it (S1)… I didn’t quite know if I dared, but then I made up my mind to do it, and I was kind of happy when I did (S14). (G5)

Academic support in terms of assistance from the teacher was one of the external resources emphasized. Having the support that allowed them to experience mastery seemed to decrease the students’ feelings of stress:

It makes me happy when a teacher helps me. It is easier to learn and more fun to learn when you understand (S2). I struggle with maths, so I often get help. Then, I feel less pressure and can relax a little more, hmmm... I kind of get more enthusiastic (S11). (G4)

The other external resource was assistance from peers. In all the groups, the students focused on this topic as an important resource that they often utilized. As seen above, students were there for each other in social situations; they cared for and helped each other during break-time. They also wanted to assist each other academically as they worked to gain knowledge. They found it frustrating to wait for their teacher and even claimed that they sometimes learned better and in other ways together with their classmates:

Sometimes I have to sit and wait for a teacher (S12). We can ask someone sitting next to us for help. They are almost like teachers... in a way. I think I learn more when I work together with others. It’s easier and more fun (S4). (G2)

Discussion

This study explores qualitative data obtained from focus groups with seventh grade students. They discuss, from their points of view, what contributes to a healthy learning environment.

We found that our data largely reflected the theoretical concept of school connectedness as described in the Wingspread Declaration (2004). The teacher was important to the students in terms of fair treatment, academic inspiration and support as well as emotional involvement. Additionally, the students highlighted the role of peers as a great resource, both in academic and social contexts, such as at break-time. The role of peers is an aspect that has received less attention in research on school connectedness.

Although previous studies have described school connectedness with two components, one typically composed of academic commitment and the other of attachment (Catalano et al., 2004; Maddox & Prinz, 2003; Monahan et al., 2010. However, our analysis revealed other nuances, wherein students expressed great commitment in both academic and social contexts. Furthermore, their stories mirrored attachment in a social setting at break-time as well as during lessons. As our data did not precisely fit the previously described components, we decided to label the main themes we identified as “academic connectedness” and “social connectedness”. In the following sections, we discuss how our findings reflect the construct of school connectedness.

Academic connectedness

In the early research on school connectedness, teachers are seen as the main source of students’ sense of connectedness to their school (Wingspread Declaration, 2004). In accordance with previous studies, our students referred to their teachers as an important resource, both in their academic work and in emotional relationships. In order for students to do their best and be dedicated in their academic work, it was vital to have a teacher who set high academic standards. Students also appreciated high academic expectations as well as the feeling that their teacher believed in their academic capabilities. It was apparent that the students also appreciated the emotional dimension of their relationship to their teacher. They expressed good feelings, self-confidence and happiness were expressed when they told stories about their teacher giving them positive academic feedback. In line with previous findings (Danielsen, Samdal, Hetland & Wold, 2009; Hattie, 2009; LaRusso, Romer & Selman, 2008; McNeely et al., 2002; Resnick et al., 1997; Samdal et al., 1998), this study confirms that the teacher is important for the learning environment and learning outcomes, not only as an academic supervisor but also as a relationship builder.

However, the students in the current study also strongly emphasized their peers as important resources in an academic context. The students appreciated cooperating on academic tasks, and they were proud to walk around the classroom helping others, in the role of assistant teacher. Through such cooperation, the students achieved active participation in their own and others’ learning process. Interacting with peers made them more committed to their tasks, and it is interesting to notice that the students expressed enthusiasm in the collaboration. Thus, the question is how their participation and use of each other as academic resources contributed to creating a sense of connectedness to school. This topic is rarely addressed in previous research on school connectedness.

Social connectedness

Social connectedness concerns the social life at school and the relations among members in the school setting. In the stories considered in this study, relationships with peers surpass relationships with teachers. Small breaks that provided fun in the classroom as well as togetherness during recess activities contributed to creating bonds between the students and prevented loneliness. Social bonds of attachment may develop when children experience opportunities for involvement and interaction (Catalano et al., 2004). Recent research (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010; Heinrich & Gullone, 2006) has shown loneliness to be strongly associated with poor health, morbidity and even mortality. As such students caring for each other ought to be greatly appreciated. It is also interesting to note the students’ ethical considerations about caring for others even though they were not close friends. At the same time, our students said that being together and sharing activities strengthened their friendship. This finding is in line with Corsaro, who says in an interview that sharing, talking or doing things together is the glue of friendship (Øksnes, 2015). Close friends may also act as a buffer against stress (Hendry & Reid, 2000). This observation emphasizes school as an important setting for forging meaningful social relationships (Voisin et al., 2005). However, there is a lack of knowledge about the role of peers in the formation of students’ social connectedness to school.

Teachers were also significant in social contexts. They were in charge of providing fair treatment, and they had opportunities of offering emotional support and other resources that our students appreciated. In addition, teachers’ respect and predictability for all students were deemed vital. These findings correspond with the connectedness theory, which emphasizes that teachers caring about their students, personally as well as academically, will contribute to strengthening students’ school connectedness (Blum & Libbey, 2004; Wingspread Declaration, 2004). On the other hand, safety, which is another of the core components in the Wingspread Declaration (2004), did not come up as a theme in the students’ discussions. The students mentioned nothing about teachers providing safety at school. Rather, it seemed that the students protected each other when necessary during recess.

The links between academic and social connectedness

In the students’ stories, there were fairly obvious links between the two components of academic and social connectedness. It seems that experiences in recess influenced the students’ academic performance and vice versa. In addition to highlighting the dimension of friendship, students emphasized on several occasions their experiences during break-time as a source of motivation to make an even greater effort in class when returning to their lessons. Experiencing social connectedness typically provided emotional motivation and energy to engage in academic tasks. In this respect, previous empirical findings broadly support students’ reflections by showing that the quality of relationships is crucial in order for teaching and learning to be effective (Bond et al., 2007; Danielsen, Wiium, Wilhelmsen & Wold, 2010; Hattie, 2009; Weare, 2002).

The fact that peer cooperation in academics seemed to strengthen relational bonds between peers deserves attention. Previous research has paid little attention to this aspect of school connectedness, Alt. Anderman (1999) has pointed to the reciprocal nature of academic and social factors in the promotion of school connectedness. As a whole, however, research has pain litlle attention to this. Academic cooperation among peers is in the hands of teachers, who may facilitate peer cooperation in the classroom and thereby promote a safe learning environment where students can participate and be of use to one another as resources.

There is a need for further studies that assess peers as a resource for each other in strengthening school connectedness. The role of peers open up new perspectives on prevention and health promotion in the school setting.

Quality and limitations of the study

One of strengths of this study is that it uses information from five focus groups that include a total of 31 girls and boys in primary school; furthermore, the study builds the students’ own experiences and statements. All three authors explored and discussed the empirical data before agreeing on the analysis presented here. In addition, we discussed the results with colleagues on several occasions. Our strategy with thorough back and forth processes and agreement on findings illustrates and supports the validity of the results (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009). Further, we have endeavoured to achieve transparency through thick descriptions (Ponterotto, 2006). However, all students included in this study were from the same school, and some may consider this a limitation. Nevertheless, and as is the case in most qualitative research, the readers need to assess the extent to which the essence of our results might be transferable to comparable settings.

Conclusion

Research on school connectedness has mostly reported on outcomes, such as better health and better academic achievements (Blum & Rinehart, 1997; Juvonen, 2006). The Wingspread consensus document on school connectedness (Wingspread Declaration, 2004) highlighted the academic as well as the emotional importance of adults for students’ sense of school connectedness. The current study questions the dominant position of adults and discusses the contribution of peers to a healthy learning environment.

The students’ stories have clarified our understanding of the construct of school connectedness. Firstly, our analysis revealed two interrelated components: academic and social school connectedness. Secondly, we found descriptions of emotional and academic concerns in both components. Lastly, and from the students’ discussions, we consider peers to be as valuable as the teacher in the development of academic connectedness and even more valuable to social connectedness. It is important to emphasize, however, that the teacher was the catalyst to releasing peer resources in an academic context. Thus, the teacher has an indirect role in addition to the obvious direct role.

The students expressed a strong wish to amount to something in life, telling us that they considered school meaningful to them. In addition, the students clearly showed that they both identified and used their own individual resources, as well as resources available in their immediate surroundings.

As the moderator never mentioned the word connectedness in the interviews, we find it interesting that students’ experiences of a healthy learning environment fit the construct of school connectedness and revealed the two interrelated components of academic and social school connectedness. Awareness of these components may be conducive to planning healthy classrooms or health-promoting interventions in schools. There is still a need for studies that explore the peer roles in school connectedness more thoroughly.

Author biography

Marit Andersen

, with Master degree in Health Promotion from University of South-Eastern Norway (USN), works at Educational Psychological Counselling Service in Horten. Andersen collaborates with researchers at the Department of Health, Social and Welfare Studies, USN, and researchers at NTNU Department of Teacher Education and NTNU Center for Health Promotion Research.

Grete Eide Rønningen

, Associate Professor at the University of South-Eastern Norway (USN), Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, Department of Health, Social and Welfare Studies. She is responsible for the USN master program in health promotion, and has long experience in research- and developmental work related to schools, municipalities and local communities.

Audhild Løhre

, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Teacher Education, NTNU. Research interests include health and wellbeing, primarily in children, adolescents and young people. Health promoting factors as well as adverse life experiences are studied. Løhre is member of NTNU Center for Health Promotion Research.

References

- Anderman, L. H. (1999). Expanding the discussion of social perceptions and academic outcomes: Mechanisms and contextual influences. In T. Urdan (Ed.), Advances in motivation and achievement (Vol. 11, pp. 303–336). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Anderman, E. M. (2002). School effects on psychological outcomes during adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(4), 795–809. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.94.4.795.

- Andersen, M. (2012). Helsefremmende læringsmiljø - elevenes stemme. Hva kan bidra til at læringmiljøet gir elevene opplevelse av mestring? Master, Høgskolen i Vestfold, Horten.

- Barber, B. K., & Schluterman, J. M. (2008). Connectedness in the lives of children and adolescents: A call for greater conceptual clarity. Journal of Adolescent Health, 43(3), 209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.012.

- Blum, R. W. (2005). A case for school connectedness. Educational Leadership, 62(7), 16–20.

- Blum, R. W., & Libbey, H. P. (2004). Executive Summary. Journal of School Health, 74(7), 231–232.

- Blum, R. W., & Rinehart, P. M. (1997). Reducing the risk: Connections that make a difference in the lives of youth. Retrived from Minnesota University div of General Pedriatrics and Adolescent Health.

- Bond, L., Butler, H., Thomas, L., Carlin, J., Glover, S., Bowes, G., & Patton, G. (2007). Social and school connectedness in early secondary school as predictors of late teenage substance use, mental health, and academic outcomes. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(4). doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.013.

- Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S. (2015). InterViews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage.

- Catalano, R. F., Haggerty, K. P., Oesterle, S., Flemming, C. B., & Hawkins, J. D. (2004). The importance of bonding to school for helathy development: Finding from the social development research group. The Journal of School Health, 74(7), 252–261.

- Danielsen, A. G., Samdal, O., Hetland, J., & Wold, B. (2009). School-related social support and students’ perceived life satisfaction. [Article]. Journal of Educational Research, 102(4), 303–320.

- Danielsen, A. G., Wiium, N., Wilhelmsen, B. U., & Wold, B. (2010). Perceived support provided by teachers and classmates and students’ self-reported academic initiative. Journal of School Psychology, 48(3), 247–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2010.02.002.

- Gibson, F. (2007). Conducting focus groups with children and young people: Strategies for success. Journal of Research in Nursing, 12(5), 473–483. doi: 10.1177/1744987107079791

- Gustafsson, J.-E., Allodi M. Westing, Alin Åkerman, B. Eriksson, C. Eriksson, L., Fischbein, S., Granlund, M., Gustafsson, P. Ljungdahl, S.,Ogden, T., Persson, R. S. (2010). School, learning and mental health: a systematic review. Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, The Health Committee.

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge.

- Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8.

- Heinrich, L. M., & Gullone, E. (2006). The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(6), 695–718.

- Hendry, L. B., & Reid, M. (2000). Social relationships and health: The meaning of social “connectedness” and how it relates to health concerns for rural Scottish adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 23(6), 705–719. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0354.

- Juvonen, J. (2006). Sense of belonging, social bonds, and school functioning. In P. A. Alexander & P. H. Winne (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 655–674). Mahwah: NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Kitzinger, J. (1995). Introducing focus groups. British Medical Journal, 311, 299–302.

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, Calif: SAGE Publications.

- LaRusso, M., Romer, D., & Selman, R. (2008). Teachers as builders of respectful school climates: implications for adolescent drug use norms and depressive symptoms in high school. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 37(4), 386–398.

- Leger, L. S., Kolbe, L., Lee, A., McCall, D. S., & Young, I. M. (2007). School health promotion. Achievements, challenges and priorities. In D. McQueen & C. Jones (Eds.), Global Perspectives on Health Promotion Effectiveness (pp. 107–124): Springer New York.

- Libbey, H. P. (2004). Measuring student relationships to school: Attachment, bonding, connectedness, and engagement. Journal of School Health, 74(7), 274–283.

- Løhre, A., Lydersen, S., & Vatten, L. (2010a). Factors associated with internalizing or somatic syptoms in a cross-sectional study of school children in grades 1–10. Children & Adolecent Psychiatry & Mental Helath, 4, 33. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-4-33.

- Løhre, A., Lydersen, S., & Vatten, L. (2010b). School wellbeing among children in grades 1–10. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 526. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-526.

- Maddox, S. J., & Prinz, R. J. (2003). School bonding in children and adolescents: Conceptualization, assessment, and associated variables. Clinical Child & Family Psychology Review, 6(1), 31–49.

- Major, E. F., Dalgard, O. S., Mathisen, K. S., Nord, E., Ose, S., Rognerud, M., & Aarø, L. E. (2001). Better safe than sorry… Mental health: Health promotion and preventive measures and recommendations (2011:1). Retrived from www.fhi.no/en

- McNeely, C., & Falci, C. (2004). School connectedness and the transition into and out of health-risk behavior among adolescents: A comparison of social belonging and teacher support. Jouranl of School Health, 74(7), 284–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08285.x.

- McNeely, C., Nonnemaker, J. M., & Blum, R. W. (2002). Promoting school connectedness: Evidence from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. [Article]. Journal of School Health, 72(4), 138–148.

- Monahan, K. C., Oesterle, S., & Hawkins, J. D. (2010). Predictors and consequences of school connectedness: The case for prevention. The Prevention Researcher, 17(3), 3–6.

- Morgan, M., Gibbs, S., Maxwell, K., & Britten, N. (2002). Hearing children’s voices: Methodological issues in conducting focus groups with children aged 7–11 years. Qualitative Research, 2(1), 5–21. doi: 10.1177/1468794102002001636.

- Ponterotto, J. G. (2006). Brief Note on the Origins, Evolution, and Meaning of the Qualitative Research Concept Thick Description. The Qualitative Report, 11(3), 538–549.

- Ravens-Sieberer, U., Freeman, J., Kokonyei, G., Thomas, C. A., & Erhart, M. (2009). School as a determinant for health outcomes - a structural equation model analysis. Health Education, 109(4), 342–356. doi: 10.1108/09654280910970910.

- Resnick, M. D., Bearman, P. S., Blum, R. W., Bauman, K. E., Harris, K. M., Jones, J., … Udry, J. R. (1997). Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA, 278(10), 823–832. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03550100049038.

- Rowe, F., Stewart, D., & Patterson, C. (2007). Promoting school connectedness through whole school approaches. Health Education, 107(6), 524–542. doi: 10.1108/09654280710827920.

- Samdal, O. (1998). The school environment as a risk or resource for students’ health-related behaviours and subjective well-being. (Doctor of Philosophy), University of Bergen, Bergen.

- Samdal, O., Nutbeam, D., Wold, B., & Kannas, L. (1998). Achieving health and educational goals through schools - a study of the importance of the school climate and the students’ satisfaction with school. Health Education Research, 13(3), 383–397. doi: 10.1093/her/13.3.383.

- Samdal, O., & Torsheim, T. (2012). School as a resource or risk to students’ subjective health and well-being. In B. Wold & O. Samdal (Eds.), An ecological perspective on health promotion systems, settings and social processes (pp. 48–59): Bentham Science Publishers.

- Voisin, D. R., Salazar, L. F., Crosby, R., Diclemente, R. J., Yarber, W. L., & Staples-Horne, M. (2005). Teacher connectedness and health-related outcomes among detained adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 37(4), 337.e317–337.e323. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.11.137.

- Weare, K. (2002). The contribution of education to health promotion. In R. Bunton & G. Macdonald (Eds.), Health promotion: Disciplines, diversity and development (pp. 102–125). London: Routledge.

- Wingspread Declaration. (2004). Wingspread declaration on school connections. Journal of School Health, 74(7), 233–234.

- Øksnes, M. (2015). You don’t have to have an internalized conception of friendship to actually be a friend. Intervju med William A. Cosaro. In M. Øksnes & A. Greve (Eds.), Barndom i barnehagen. Vennskap. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.